Patrick Tunney was a poet and songwriter from Cushlough, Westport. Over his lifetime he penned and published over one hundred and twenty songs and poems which have been recited, recorded and performed many times. He wrote about life at the time in poems such as ‘Drummin long ago’, ‘The Widow from Mayo’, ‘I bought my ticket at Westport Station’, and ‘Leenane by the sea’. He captured the history of Ireland’s struggle for freedom as it unfolded in front of him and of his time spent in prison in poems such as ‘The Curragh camp dream’, ‘My Frongoch Companions’ and ‘Banba was betrayed’. He also recorded the life story of various significant figures of the time including Roger Casement, Mick O’Brien, Joseph Gill, Sean Corcoran, Margaret Malone and Mary Mulroy.

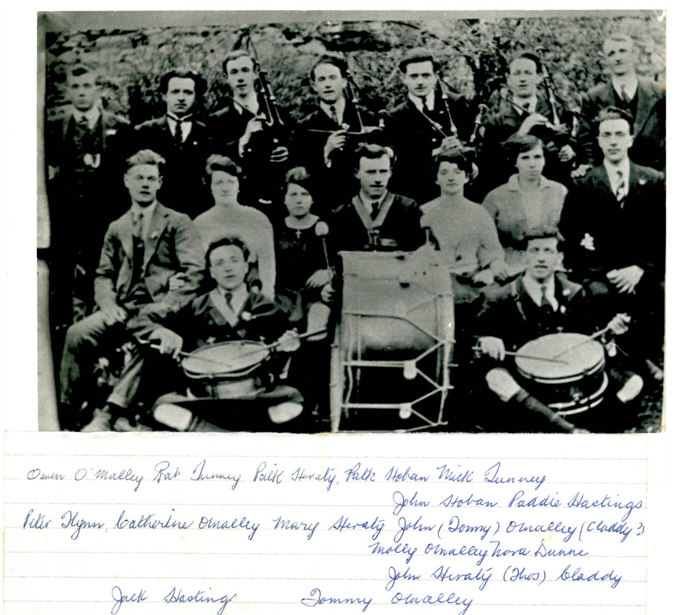

Patrick Tunney was born in 1887 to Margaret and Thomas Tunney of Derrykillew, Cushlough, Westport. By the time his father died in 1915, Patrick and his brother Michael were heavily involved in the Irish Republican Brotherhood (I.R.B.) and in the fight for independence for Eire. Tunney strove to organise the movement throughout Mayo and set up the first branch of the Gaelic League in Cushlough in 1913. That same year he set up the Cushlough Fife & Drum Band. Three years later, in 1916 the band had the honour of heading the parade on St. Patrick’s Day. They marched from the Octagon to Westport Railway Station to meet The O’Rahilly who was coming to address a meeting in Westport that day (The O’Rahilly was killed in Dublin during Easter Rising only a matter of weeks later). In 1918, Tunney led the band at the trial of Mr. Ned Moane from Westport and William O’Malley from Newport, on that day the band were attacked by the Royal Irish Constabulary (R.I.C) on Castlebar street. Some band members were so severely beaten that they had to be hospitalised. Their drums and fifes which they used in self-defence, were no match for the batons of the R.I.C. That event saw the permanent demise of the band.

Tunney joined the Irish Volunteer movement at its inception. Following the Easter Rising of 1916 in Dublin, Tunney was mobilised with the Westport Battalion. Under Joseph McBride they marched from Fornaught Hill into Westport Town. In his article “FROM DERRYKILLEW TO FRONGOCH”, printed in The Mayo News in 1918, he reflects on his arrest for this.

“The golden rays of a glorious summer’s sun were just brightening the heavenly canopy on Tuesday morning the 9th May, 1916, when I suddenly awoke from my slumber to the tramp of marching feet, which were fast approaching my parental home, to the door of which a gentle knock was immediately given. My time for consideration seemed limited then. Whilst still barefooted I instantly opened the door and I was more than a little surprised when I saw standing outside three armed Constables with Sergeant Coughlan, Carrowkennedy, and Head Constable Creighton, Westport”.

This began a life where he would see the iron bars and barbed wire of no fewer than twelve different jails in England, Wales and Ireland. Starting in May 1916, with the R.I.C. barracks in Westport, to Castlebar Jail, Trinity College, Stafford Detention Centre, Richmond Barracks, Dublin, Wandswork Detention Barracks – Surrey County Jail, Frongoch South Detention Barracks, Wormswood Scrubbs Prison, London, and in the North Frongoch Camp, Merrioneth, Wales. Then later in Galway jail, Eglington Barracks and Rath Camp in the Curragh. He saw the inside of some of these jails on many different occasions. He was treated appallingly during his time in prison, including one beating in Galway prison which was so bad he never recovered and carried a limp for the rest of his life. Likewise he was tortured in Rath Camp, the Curragh. However, in September 1921 he was part of a group who made a successful escape from the camp. It was during his time in Frongoch Camp that he came into contact with the immortal Terence MacSwiney who was his dormitory leader.

In 1917, just six months after his release from Frongoch jail, Tunney married Nora Dunne from Carrakennedy, Westport. They would raise ten children on a small farm in the barren, rural setting of Derrykillew. Their home, in the mountains south of Westport, was headquarters of the West Mayo Flying Columns which was continually frequented by the members of the Active Services Units of the Irish Republican Army from 1917 to 1922. These men on the run found a warm welcome under their hospitable roof. On this account the Tunney home was often raided, sometimes twice in one night, by British forces. They were threatened with death more than once when they would not give the required information about the movement of the ‘boys’. The gable ends of their family home bore the marks of British bullets.

One brutal episode occurred on the 22nd March 1921 early in the morning. The Black & Tans arrived at their home and to their surprise they found Patrick Tunney there. They had believed him to be under lock and key in Galway jail. However, Tunney had been granted a ten day parole from Galway jail because of special family circumstances. The Black & Tans pinned him at gun point against the gable wall of his home with the intent to execute him on the spot. And thanks to the cries of a tiny newborn baby from within and the pleading of the family he was spared. Nora had just given birth to her third baby, a girl, Margaret Mary (Mairéad) late the previous day. Patrick Tunney was advised for his own security to return to the ‘safety’ of Galway jail. It would be another nine months before he would lay eyes on his wife and baby again.

Tunney went on to become the first treasurer of the West Mayo Executive of Sinn Féin and later the clerk of a Sinn Féin court. In 1928, he stood as a Fianna Fáil candidate in the Westport area in the County Council Election.

Tunney was a tailor by profession, but this was not a sustainable occupation in rural Ireland in the early 1900’s, so he was encouraged to leave his family and tiny farm behind. He moved to Dublin where he lived in Ballygall Road, Finglas. He secured a job as a relieving officer in Store Street, Dublin. It was his job to assess the needs of the underprivileged in inner Dublin and to assign to them monetary support. On many occasion, Tunney gave of his own wages to support people who were in greater need. Outside of work, he continued his active interest in the fight for nationalism. His daughter, Mairéad reflected on this time stating:

“I remembered at our home in Ballygall road seeing all kinds of long and small guns. There were small revolvers that would fit easily in your hand. They were all shining and stacked in a line in the shed at the back behind the coal & timber. There was around 50 guns that were stolen from the magazine port in the Phoenix Park. My Dad came home to Derrykillew with Christmas presents. The Guards followed him and questioned him about the movement of people in Dublin. The next day the guns had disappeared”.

In May 1933, he was nominated by Fianna Fáil to contest the County Council elections for the Finglas area. He was Secretary of the Mayomen’s Association in Dublin and a founder member and Secretary of the Dick McKee Memorial Pipe Band. Patrick Tunney died in Dublin in 1951. It was a co-incidence that on the day of his funeral, Eamon de Valera unveiled a monument to the memory of Dick McKee in Finglas, Dublin.

In 1951, The Irish Independent described Patrick Tunney as “a prolific writer of patriotic ballads, articles and letters”. He was an ardent nationalist and a prolific contributor to local and national newspapers having over seventy articles published. His views forthright and direct. In an article in the Western People, he expressed his views on Ireland and the Black & Tans where he wrote “Banba’s sons were never defeated, but on all occasions were outnumbered, when England dispatched hordes of the lowest scoundrels she could recruit together from her jails and criminal lunatic asylums with orders o loot, burn, desecrate, assassinate and conquer”. His letters were often controversial and provoked reaction and replies, but Tunney stead-fast in his conviction.

The Mayo News described his passing as

“a shock to his legion friends and it removes yet another colourful figure of the Fight for Independence period”. The article reported that “his funeral arrived at Cushlough on Saturday evening by road from Dublin and was met by a thousand people from Westport and Drummin areas. After Mass on Sunday, interment took place in the nearby cemetery. His old comrades of the I.R.A. rendered full military honours at the graveside where an oration was delivered by Brigadier. Ed. Moane, West Mayo Brigade, Old I.R.A”.

Margaret Mulroe and Nora Dunne

These two women suffered greatly as a result of the direct involvement of Patrick and Michael Tunney in the fight for freedom. Their home in the mountains, south of Westport, was the headquarters of the West Mayo Flying Columns of the I.R.A. Their home was an easy target for the British forces which the raided with unparalleled frequency. The two women were taken out and threatened with death several times.

Margaret Mulroe was a native Irish speaker from Greenáun, Tourmakeady, Co. Mayo. She married Thomas Tunney, Derrykillew, Cushlough, Westport. These were the days of matchmaking. The ‘deal’ was done at The Pattern in Leenane. That was the first time that either set eyes on the another. Thomas Tunney was twenty one years older than his wife died 1915. At that point her two sons Patrick and Michael were heavily involved in the Irish Republican Brotherhood and independence for Eire.

In 1916 her home was a hive of republican activity. Liam Mellows, the Galway leader, found a warm welcome when he stayed with the Tunney home in Cushlough. Mellows was on one of his organising trips to Aughagower, was astounded to find that the Hall was in fact a strong I.R.B. centre and was amazed by the organisation of the Cushlough brigade. At the height of tension, Tom Ketterick brought rifles, revolvers and ammunition by truck to the Tunney homestead in Cushlough. The supplies had come from England by train via Maam Cross. They were distributed by Tunney to the local members of the Sin Fein columns.

In 1917, just six months after his release from Frongoch jail, Nora Dunne, Carrakennedy, Westport married Patrick Tunney. She married not alone her sweetheart but married she married ‘a cause’. Her husband was a ‘man on the run’, tailor, a poet, a songwriter and a small farmer. Unfortunately poems and being on the run don’t put a dinner on the table. Nora was to raise ten children on the small farm in the barren rural area of Derrykillew, while he spend many years of his life in jails through-out Ireland and England. Later on her family would endure the hardship of seeing her young family split between Derrykillew and Dublin.

Nora was a member of the Cushlough Fife & Drum Band. She marched with the band in 1916 when the band led the parade on St. Patrick’s Day in Westport and a month later on the day that The O’Rahilly addressed the famous meeting in Westport.

Nora and Margaret were true patriotic Irishwomen. They were true to their family, community and true to the traditions of ancient Ireland who put the freedom of their country before everything earthly. The valley in which they lived being isolated was continually frequented by the members of the Active Services Units of the Irish Republican Army from 1917 to 1922. These men on the run found a warm welcome under their hospitable roof, but it also attracted ‘visits’ by the Crown forces who sought information about the movement of the ‘boys’. The gable ends of the Tunney family home bore ample proof of these visits with many the marks of British bullet.

One brutal episode occurred on the 22nd March 1921, when in the early morning, the Black & Tans arrived at their home. To their amazement they found Patrick Tunney there, who they had believed was under lock and key in Galway jail. The Black & Tans didn’t know that he had gotten a ten day parole from Galway jail because of special family circumstances. The poor mother, Margaret, saw the Black & Tans pin her son at gun point against the gable wall of his home. Their sole intent was to execute him on the spot. And they would have carried it out had it not been for the cries of a tiny new-born baby from within and the pleading of the family. This is one of the very few occasions where the Black & Tans showed any since of compassion. But, that compassion was short lived.

They broke into their home despite the pleas of the family that the mother had just given birth. Nora had just given birth to her 3rd baby late on the day before. The baby, Margaret Mary (Mairéad) Tunney would grow up to become a renowned poet herself. The Black & Tans went up to her bed-room and pulled the bed clothes off her bed, in case she was hiding a fugitive. The grand-mother, Margaret, boldly refused to converse with the Black & Tans in a language that they could understand. So the hit her with the butt of their rifles and knocked her against the dresser, injuring her and breaking much of the delft. They smashed her spinning wheel and burned it in the fire. Patrick Tunney was advised for his own security to return to the ‘safety’ of Galway jail. It would be another nine months before Nora and her baby would lay eyes on him again. In the interim, a truce would be called and the treaty signed. It was during this time also that Patrick Tunney planned and participated in a historic successful escape from the high security Curragh camp in September 1921.

When Margaret and Nora died their contribution to Irelands cause was honoured by large attendance of mourners and many leaders of the fight for freedom. Margaret’s coffin was carried shoulder high from her home to Cushlough church where we son Patrick recited the Rosary. The family received mass card and telegrams from Liam Cosgrave, T.D. Secretary to the Taoiseach, the High Commissioner for Australia (W. J. Dignam and Mrs. Dignam) and from the Cathaoirleach and staff of Seanad Eireann; W. Davin, T.D. Dun Laoghaire.

These were the women behind the men, the often forgotten people and the unsung heroes. Those two ladies faced down the rifles of the R.I.C. and the Black & Tans brutes for the cause of Irelands freedom.

www.westportheritage.com

www.westportheritage.com