The Rising and my Dismissal.

Elizabeth Bloxham

I was in the North when I read news of the Rising in the Evening Telegraph. Though I knew from a talk I had with MacDonagh the previous summer that things were coming to a head I was shocked into a state of unreality by the bald report in the paper. There was no one to whom I could speak of the matter. I remember meeting a man with whom I was acquainted; he stopped me in the street to say, “We all know you are a home ruler but of course we are sure you are horrified at what has happened in Dublin; you wouldn’t have anything to do with the like of that”. The surface of my mind knew that this man was sounding me; in what he thought was a cute way, so that he could report my reaction. I looked him in the eye “You are one of Carson’s men”, I said “and you’ve often said that ‘Ulster will fight and Ulster will be right’; if Carson ever fights would you go back on him?” “I would not” he said indignantly. “Well then”, I said, “how dare you think I’ll go back on my side; I only wish I had been in Dublin to give the Volunteers any help that was in my power”. Another man approached me on the same lines and got the same answer.

I was deeply preoccupied with the great and tragic event that was taking place and though, as I said, the surface of my mind was aware of their motives in speaking to me they made no more impact on me than does a stinging fly which one brushes aside and forgets. In the house where I lodged there was no mention made to me of the Rising and I exchanged the usual every-day talk with the members of the household. Then came the time when each day’s paper brought news of the executions. I made what I thought was a successful effort to hide my feelings from people who I knew were unsympathetic. But later on the woman of the house told me that whenever she entered my room at that time s he felt I was as one watching by the dead. I said I thought my manner to her was the same as usual. “It was”, she said, “but I knew that the moment I closed the door you were again watching by the dead”.

There was great agony of spirit in Ireland at that time. My teaching work went on as usual but when the session ended in June I got a notice of dismissal for which no reason was given. By the same post I received a letter telling me of the dangerous illness of a young relation of mine and the tears sprang to my eyes. I quickly remembered that I dare not cry; I had to do shopping in the town for I was leaving Newtownards for good the following morning and a tear-stained face might be misinterpreted as the result of my dismissal so with a resolute effort I put away my private grief. I designedly went into the shop of a member of my Committee and made my purchases in the usual manner. The owner of the shop seemed ill at ease and became more so when I said conversationally, “Well, Mr. D., your committee have taken away my position but it isn’t in their power to take away my principles and, of course, so long as lam true to them nothing else really matters, and I bid him good morning pleasantly.

I knew what I said would be repeated as I meant it to be. The chairman of the committee was an intelligent man of good education who, as I felt sure, did not share the narrow outlook of its members. I met him on the road as I was cycling back to my rooms. I dismounted and faced him. I told him I had received his notice of dismissal that morning. I reminded him that he was the man who had thanked me so effusively for my sacrifice in staying in Newtownards at a time when I could have got a more suitable position elsewhere, and I recalled to him his earnest hope that I would never regret the decision I had made solely in their interests. He had no defence except the foolish remark that that had nothing to do with my dismissal but I pointed out incisively that if I had taken the position which suited me it would not now be in his power to dismiss me, “But”, I said, “I take this as a shining example of the Civil and Religious liberty which you in the North love so dearly”, and I rode away without even saying “Good morning”, from which it will be seen that I felt more hardly to him than to the shopkeeper, for he was an enlightened man (or so I thought) and I expected more from him than from the narrow-minded.

I feel sure that my short conversation with him was NOT repeated to anyone. In point of fact although I spoke so strongly I never felt any deep sense of grievance at my dismissal for I am sure that if one outrages popular feeling in any community as flagrantly as I had done some such repercussion is bound to ensue. Later on I wrote to the head Inspector in the North asking him to investigate the cause of my dismissal. I did this merely because I wished it to be on record why I had to leave in case the Committee would frame up some bogus excuse for their action. His reply was most courteous and complimentary to me. He praised my work and ability but said that a committee were within their rights in dispensing with a teacher without giving any reason and consequently the Department could not question their action. He assured me that neither he nor the Department regarded my dismissal as any reflection on my competence as a teacher.

I then wrote to the Principal of the school for a reference and he sent one which bore testimony to my ability as a teacher, my power of organization etc. Some years later I received a form from (I think) a Sinn Féin body. This form was to be filled by stating if I had personal knowledge of anyone who was penalised for national activities. I searched my memory but could not recall any instances of which I had personal knowledge and, so far as I remember, I left the form unanswered. I do know that at the time I quite forgot that I belonged to the category of those who were penalised. This may seem odd but it must have been due to the fact, which I have already stated, that I cherished no sense of grievance, and. at a time when men and women were risking their lives it seemed to me, as it still does, a trivial matter that one should lose one’s job.

I now write these details because I have been asked to do so in the interest of those who, in time to come, may wish to have sidelights on the great event which made a vital change in. the history of our country. During all the time I was in Newtownards there were only one or two small happenings which got under my skin. When I first went to the North I was very curious to get into touch with the mentality of the Orangemen of whom we in the West had tidings but failed to understand. It was the sort of interest one might have in a strange plant if one were a botanist. Could people really and truly believe that we in the South and West would persecute them if we got the chance? It was unbelievable but I would try to fathom the mystery by studying the psychology of a people who were supposed to have this strange obsession.

Luck was with me. The driver of a bread van called at the house in which I lodged a few times each week. He was an Orangeman and I got on speaking terms with him and we became friendly. He was shocked to hear I was a Home Ruler and he, being a religious man, wondered how I would dare to face my God if I died holding such opinions. I, of course, didn’t try to reason with Johnny. I was too interested in glimpsing the strange convolutions of his mind. I found be visualised a scene in which a loyal Orange family were listening to a chapter of the bible being read by the father. Everything was orderly and peaceful until wicked Home Rulers came in the night and “waded knee deep in the blood” of these harmless folk. I was satisfied I had got a key to the outlook of Orangemen of his type and did not go out of my way to have further conversation with Johnny. But if I stayed in my room I could hear him asking, “Where is she to-day?” He said he liked my “crack”. So friendly did we become that, in spite of my sinful polities, he avowed that he would speak to me whenever he met me. This amused me but I afterwards discovered that he was frequently reproached for saluting the like of me. But after the Rising I met Johnny driving his van and he averted his head and broke his knightly vow. That got under my skin. The Principal of my school had a little son that I was rather fond of. One day in a lonely place I saw them coming in my direction. I knew the Principal would not speak to me so I turned to the little boy with a friendly word but the child turned his head in the other direction and that too hurt me.

This is an excerpt from Witness Statement WS0362 made to the Bureau of Military History.

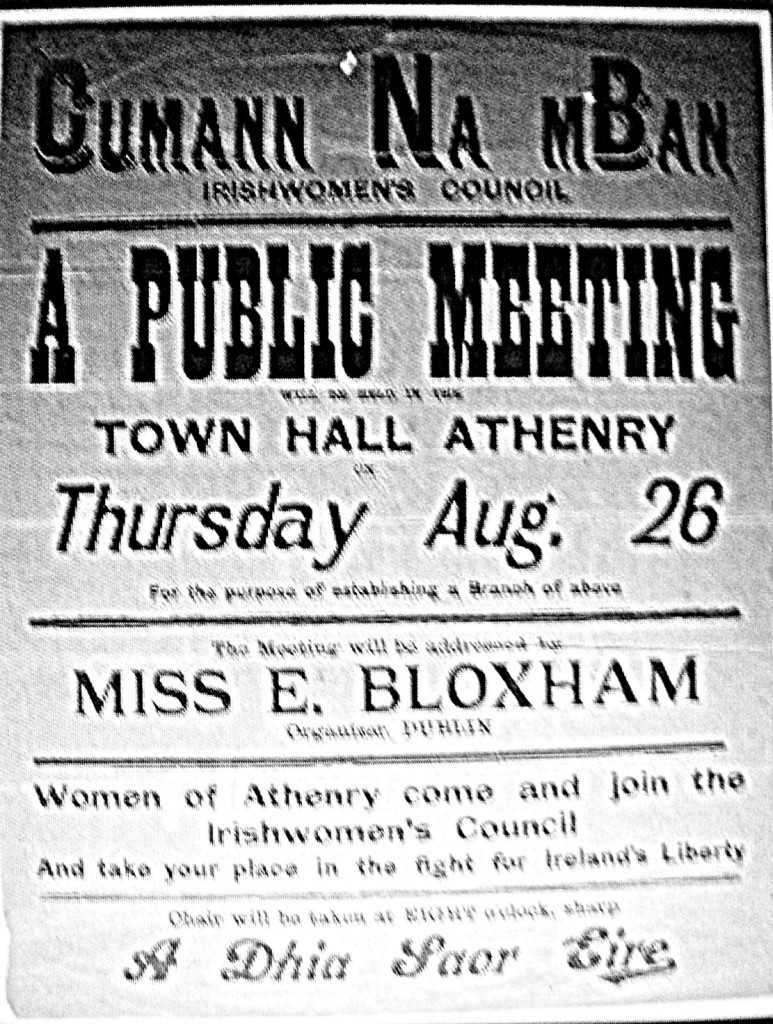

Elizabeth (Bessie) Bloxham was born in 1878. Her father, on retirement from the Royal Irish Constabulary, lived and worked on the Westport House Estate. Elizabeth went to Dublin in 1908 to train as a domestic science teacher. There she became involved in literary and feminist circles, contributing articles to Irish Review, United Irishman, Irish Volunteer and others. As a founder member of Cumann na mBan she was its chief organiser in her spare time. The Census of 1911 shows her living in Newtownards, Co. Down, where she taught. After her dismissal in 1916 she worked in Meath and later Wicklow.

www.westportheritage.com

www.westportheritage.com